This is part 2 of an interview I conducted with my From the Ground Up cofounder, Mylo. You can read part 1 here.

Also, there are references throughout the conversation to a Black Lives Matter protest Mylo and I participated in the day before this interview took place.

E: One of the things I write about on the blog a lot is how some of the principles behind how religious organizations are run can be very useful for building activism communities, especially in the sense of how… like almost everyone we saw at the protest yesterday was under 30. Right?

M: Mhmm.

E: How do you envision From the Ground Up and/or activism communities at large functioning better or in such a way where we don’t just have a bunch of 20-somethings? Because, I don’t think we will fix anything with that little slice of the population.

M: That’s a good question. What does it have to do with religion?

E: Churches are really good at providing childcare and doing things that enable people over 30 to do stuff.

M: Yeah, that’s interesting. I guess that is a barrier. I mean that’s interesting because I think there’s a lot of reasons why there aren’t a lot of people in their 30s and 40s, 50s, 60s, 70s who are going to protests. But also, I’m sure that there are people engaged in organizing who aren’t going to protests who are in that age group that you just don’t see.

This guy that I bumped into.. Did I tell you about this? I was going for a bike ride, and I stopped at a little free library that was in front of a Jewish community center called Havurat Shalom. This guy who was maybe in his 70s was just like “Hey! What’s up?” and started asking me questions. He worked there. He said, “I’m really involved in the Defund SPD movement and tenant organizing in Somerville.” And I thought, this is this cool 70-year-old Jewish man doing organizing in Boston. And normally I don’t assume that people in their 70s are organizing. Anyhow, that was cool. I feel like I really want to talk to him and have him answer this question.

So, you know I am a little bit uncertain about how I feel about protests, marches, rallies like this idea of to show support you’re going to walk for five miles and drive around a lot. And I was so mad yesterday when the person said, “Can you all go faster?” And I thought Are you fucking kidding me? Can we go faster? I think we’re going at a great pace. Clearly, my friend here is in a wheelchair and just… what? Do you want this to be accessible at all? I was so angry.

I think we need to have events that… I think giving access to childcare is a great idea. The first campaign I ever worked on was a childcare campaign when I was in college. It didn’t go that well…

E: [giggles]

M: Swarthmore. Anyway, I also think that a lot of older folks feel very alienated from younger folks because they feel like we’re so hung up on language. If you say the wrong word, you’re cancelled. And I think that makes people not want to be involved.

I don’t really know though. I think outside of that I have to think about this more. What do you think? Oh, I can’t ask you.

E: Sure you can, I guess. It doesn’t surprise me that the old man you met was working out of a religious institution. They are very good at doing organizing across generations. I know that we don’t think of Evangelical Christians as activists because they are “the enemy” or whatever, but they are so good at it. They know how to do it with children and with 85-year-olds. They just know, which is why they are so effective.

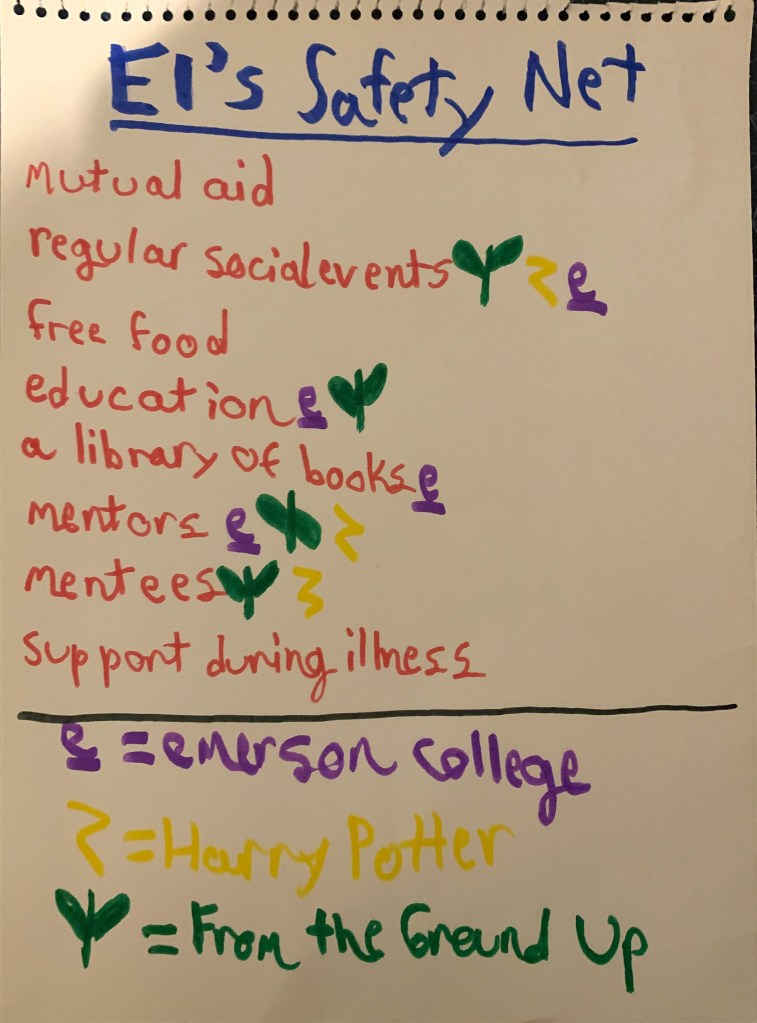

M: I know that as part of her work with the JLC, Emma [Mylo’s girlfriend] works with the social action committees of different synagogues, and they all have one. Even my mom works for the Bridgeport Mission, which is a very religious organization. The organization helps house women and children that are coming from households with domestic abuse. I think that a lot of religious organizations are doing that day-to-day, make sure that you’re fed, make sure that you have housing kind of work, whereas a lot of folks in their 20s are caught up in this intellectual… like Marxism, what is the right term, we’re the revolution, let’s make sure everyone has the right perspective, but aren’t doing as much of the “like do people have food?”

That’s why I want to learn a lot more about the Black Panther Party, so I’m reading the autobiography of Assata Shakur. They were trying to play both roles of making sure people’s basic needs were met and also putting forward a platform with a long term vision. I think that’s really important because I think I find it frustrating that so many of the people we want involved… if we want like people of color, working parents to be involved in organizing there needs to be a way for them to be involved that aren’t many, many hours of work or very intensive. You need to be able to fit with people’s schedules and their lives and support their kids. They have to feel like their lives are going to get better soon and not like one day after the revolution.

Yeah, good question. We should keep talking about this question.

E: Where do you hope you and/or FtGU will be in five years?

M: Well, everyone knows I want to be really famous.

E: [rolls their eyes]

M:Yeah, no. Where do I hope to be in five years? That’s a good question. I don’t know. I feel like I never know where things are going. You know what I would like? Here’s something I was thinking about: I think that right now there’s all these social justice organizations in Boston. There’s Defund SPD. There’s FFC. There’s FTP. There’s MAAPB. I want to feel like, in five years, that we’re one big community. Like those orgs, plus all of the climate change orgs… I want it to feel like there’s an organizing hub in Boston, and everyone knows each other, and likes each other, and supports each other. And we’re not fucking competing for the same collection of people. That’s the thing I’m trying to figure out. We’re all organizing in different ways for different issues, but there really is no point in there being like four racial racial justice/defund orgs. Like why? [laughter] It doesn’t make any sense. And then they’re like “oh, there’s a protest” and there’s another protest and another protest. That’s not forward momentum. You need to have a protest and then pull people in to your org to be doing something.

So I think what I want is for all of the orgs to be working together, and also for there to be ways to get involved that are very easy and clear. And that can be different depending on what you can do. Because right now I’ll ask to join a thing and they’ll say “You can volunteer.” And you don’t want to volunteer; you want to be in it. You want to be part of this community of people. I want to be part of that shift in Boston where it feels like there’s an organizing community, and it’s constantly growing. People want to be a part of it. Rather than like, “Oh someone died, and now I have to organize and go to a protest so that my Black friends think that I’m woke.” That’s the mentality that I find frustrating.

So I don’t know if I want FtGU to get really really big or if I want it just to be that connecting glue between different organizations. And I want to be taking care of myself and eating three meals a day and really buff, and I want to be taller.

E: That won’t happen.

M: Says who?

E: [laughs]

M: I was thinking of buying a house in Maine, but then I couldn’t be organizing in Boston. Maybe I could though. Those are all of my thoughts.

E: Yeah… to wrap things up, I write a lot about how I could not do this without you. I am wondering how you view the way that you and I are very different… We have similar outgoing personalities, but I think we’re very different in the ways we do work. How do you think we work as a team?

M: Good question. One of the many things I really appreciate about you is that you care enough about this to do it even when it’s not easy, even when you’re really tired, which self-care? I mean it’s hard to find balance, but both of us do this work even when we’re wiped out sometimes. I think that sometimes we have to tell each other to stop. That’s important. But mostly it makes me feel like you actually care, and you’re not just doing it for the points. You’re not just doing it this week.

I think in terms of how we work together, I think we both work really hard. I know that you’re my warrior.

E: [makes noises of emotion]

M: I push you to try to go for stuff sometimes, even though it might not be great or perfect, and I think you try to make sure I don’t do anything really dumb.

E&M: [both laugh]

M: Because I’m always like, “I had this great idea in the shower, let’s do it all today.” And that’s fine sometimes. It’s fine to mess around, but you do have to be careful. I think you help me make my good ideas into better ideas. And then so much of it is in how do we get there. I think I’m getting better at the follow through part, but you’re also very good at it and good at figuring out how to get into the details.

I feel like people don’t understand that organizing isn’t just about showing up at the protest, and it’s not about having a protest or having a meeting. It’s about all the little things like what questions are going to be asked, who’s taking notes, are we going to do breakout rooms, how are we gonna collect people’s contact information. There are just so many little pieces that if you really think through them well it can make an event go really well. If you don’t think through them at all, you came together and you talked, but did anyone get anything out of it? Are you moving the movement forward at all? I don’t know.

I think that both being able to have a lot of good ideas and build on each other’s ideas, and also put them into action is something that we do well together.

E: Thanks Mylo!

M: You’re very welcome!